RequireJS and Backbone on a Single Page Application - Part 1

November 4, 2015 by Vinicius Isola

Building single page applications isn’t easy. As the app grows and gets more complex your Javascript code gets harder to maintain and duplicate logic start spreading all over the place. Breaking your code in well defined and self contained small modules help to keep the complexity low and organize the logic in an encapsulated and predictable way. But to do that it means that you now need some kind of dependency management system in place.

RequireJS helps you with that. With it, creating new modules is as easy as calling a function and declaring dependency is as easy as passing an argument to that function.

But managing dependencies is just part of the problem. You still have a lot of code to make requests to your REST APIs, handle the rendering of the content on the page and user interactions.

Enter Backbone, a Javascript framework that has many of those basic features every app needs. It also helps with the task of organizing your code and keeping clear separation of concerns.

In these two blog posts (the one you’re reading and this) I’m going to show a simple example of how to configure and use these two frameworks together in a way that makes it really easy to build well separated and reusable components. On the first post I’ll talk about how RequireJS works and how to configure and use it. On the second post I’m going to show how to add backbone to the mix and how to organize the code in a way that it’s easy to maintain and extend.

The code for this post lives in my Blog’s GitHub repository under require-js-backbone.

How RequireJS works

RequireJS provides you with two basic features: defining a module and declaring a dependency with another module. And to use it, you only need to understand two simple functions that are very similar: define and require. The first function is a way to declare a module and let RequireJS know what dependencies that module needs. The second is a way to tell RequireJS that you need some modules to execute some piece of code but you’re not declaring anything (no new module). In their most common form, they have the exactly same form:

require/define ([array with dependency names], callbackFunction)

Let’s start with a simple example where we define a router module. Ideally we have one module per file so that it’s easier to find it. It also means that you normally have all the code in a file wrapped on the callback function passed to RequireJS. The callback function gets passed in all the dependencies as arguments in the same order they were declared. Back to the example:

define(["backbone", "jquery"],

function (Backbone, $) {

// Do something with jQuery and Backbone in here

//...

return new Router(); // This is your module

});

In this code we are defining a module - that will have the name of the file (router.js) it’s in by default - that has a dependency with the jquery and backbone modules. RequireJS will look in its registry and build a path where those files needs to be loaded from and make a request for each. After loading and executing the loaded dependency (and all dependencies of your dependencies, recursively) it will call the callback you provided passing what was returned by jQuery and Backbone modules to it.

Since the argument variables in your callback are local they can be giving any name you’d like. Inside the callback we use our dependencies and return what will become our module. In this case it is an instance of a class called Router. It could be the class itself but in this case we want to have only one instance of Router in the application - each module is cached by RequireJS so it won’t be loaded nor executed again.

The other way to use RequireJS is the require function. As I said, it has the same format but the return value will be ignored. Let’s use the module we just defined:

require(['backbone', 'router'], function (Backbone, router) {

// Do something with Backbone and router here

});

As you can see, the code is very similar. The only difference is that since we’re not defining anything new we can just use the dependencies we declared - you don’t need to return anything.

What’s in this project?

This project uses some other frameworks and libraries. Below is a list of all of them, why we need them and a link to where you can get them:

- RequireJS - this is the framework I’ve been talking about

- Underscore - provides a bunch of helper functions and also a very fast and simple templating engine. It’s also a Backbone dependency

- Backbone - already talked about it, I’ll explain better in the next post

- jQuery - the world famous Javascript framework, also a Backbone dependency

- Text - plugin for RequireJS to load text as modules. tpl (next item) depends on this

- tpl - plugin for RequireJS, this is going to render the templates using Underscore Templates

Configuring RequireJS

With all the code in place, you can setup your index.html page. This is going to be the page where everything is going to be loaded from - the single page in your single page application. What you need to add to it is: the basic html structure where your app is going to render on, styles and links to css files and one single script tag like the following:

<script data-main="/js/main.js"

src="/js/lib/require-2.1.20.js">

</script>

There are two important things in this script tag: first, it loads RequireJS (the src="/js/lib/require-2.1.20.js" part) and second it tells RequireJS where our initialization script is (the data-main="js/main.js part).

When it finishes loading, RequireJS will load the script you point it to (the initialization script) and run it. That’s where you’ll do all your configuration and put the initial code that will bootstrap your page. This is the configuration part of what’s inside js/main.js:

require.config({

baseUrl: '/js',

paths: {

'backbone' : 'lib/backbone-1.2.3',

...

'template' : '/template'

}

});

This is telling RequireJS where to find the library scripts and where all the project’s javascript code goes. RequireJS uses this configuration to create its module registry and to determine where to find each module.

The first thing we’re setting up is the baseUrl. This tells RequireJS to search relative paths based on that directory. This means that if you require a module called model/Contact, it will prepend it with that directory and append the js extension to it. At the end it will make a request to load /js/model/Contact.js.

The paths object in the configuration will tell RequireJS to map some strings to specific paths. Since all libraries have version numbers and are stored in a lib directory - for better organization, standardization (all lower case) and to keep migrations to different versions easier - this part of the configuration maps each library to its correspondent path - also, internally libraries refer to themselves with shortnames since they don’t have a way to know where you’re storing your libraries, so you need this to make tpl and Backbone work. The paths on the right hand side load like normal modules, which means that they will be prepended with baseUrl and appended with js extension by default.

Absolute paths won’t get the baseUrl prefix. In this case we’re setting up a mapping to make it easier to load templates. Template files go into the /template directory, outside the js directory, so we have to make that a logical path. Setting up a path configuration for it will let us use this logical path instead of the real (absolute) folder structure. That also helps when moving things around.

Folder structure and code organization

To organize and separate project code from libraries, all libraries go inside a lib folder. Storing them with the version numbers is also a good idea because it will make it easier to figure out what version of what library is being used. Setting an all lower case with no version alias to each library make it easier to update to newer versions and to remember how to refer to them. Updating to a newer version would be just dropping the new version in the lib directory and updating the main.js to point to it.

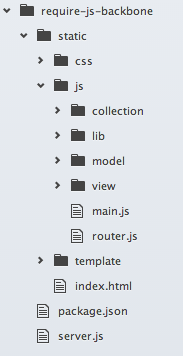

This is how the folder structure of the project looks like:

In this project I’m using node.js and express to create a simple backbend. The part that we’re interested on for this post (and the next one) is the static folder - where the static code goes into. You can see that index.html is in the root of the static folder. All Javascript goes inside the js folder, css files in the css and templates in the templates folder. Inside the js folder there’s a bunch of subfolders to separate the files even further. You can see the lib folder where all the libraries are stored.